Which brings me to the last painting in this Town House in Lockdown exhibition. It’s by James Mackinnon and it’s an appropriate one to end with as the very first piece of East End art I encountered was by James. It was a long while ago in 1994 and ‘London Fields East: The Ghetto’ was an exhibition at the Museum of London and the memory of peering in through the windows of that extraordinary model of Ellingfort Road in Hackney stayed with me for a long while afterwards. The street was due to be demolished, but was being occupied by squatters at the time, many of them artists.

So, as my journey with East London art started unwittingly with a piece by James Mackinnon, it feels fitting that this lockdown exhibition should end with his Tower at Night, London Fields from 2012. It was the last in a series of paintings of the area around London Fields where he used to live.

To me this has that magical sense of a perfectly still night, that beautiful moon shining, not a breath of wind, like some of the beautiful nights with a spectacular moon we’ve had in lockdown. No cars out, or people walking around but the sense that people are still there in a multi coloured patchwork of urban life. When I stood in the gallery and looked at this painting I wondered what it would look like if someone switched those lights off….

As soon as lockdown started, I really wanted to to cycle into central London to see it as I’d never seen it before. I expected to find it rather beautiful, the buildings, uncluttered by hordes of visitors, finally revealed in all their glory. Instead I found it very sad, depressing even. The doors of St Paul’s were tightly shut with no one on the steps, just one other cyclist there having a look. Unlike this painting there was no lit window to reassure me that there was someone inside, that life was carrying on as normal. This was very definitely not normal and it made me realise that beautiful as they are, these city landmarks are made by the presence of people. The loss of that same buzz of visitors that I’ve noticed in my empty shop is magnified many times over looking at a tightly shut and desolate St Paul’s.

Which brings me back to Doreen’s Mile End Park. I’ve realised that because it doesn’t look like a city view, I don’t feel the need to find people in it, to see life going on behind the façade; it feels rural rather than urban. It’s the city views that need people, without them they are sad, just as central London has been sad in these terrible last weeks.

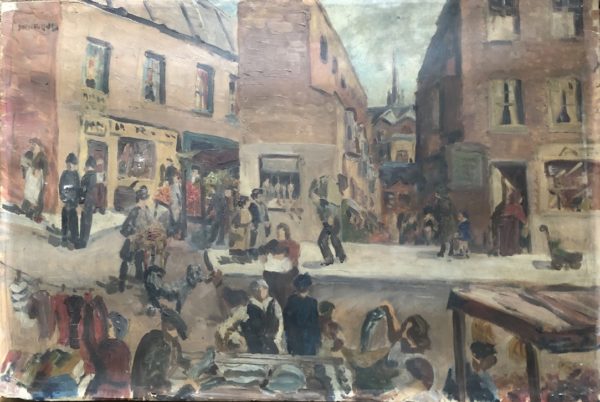

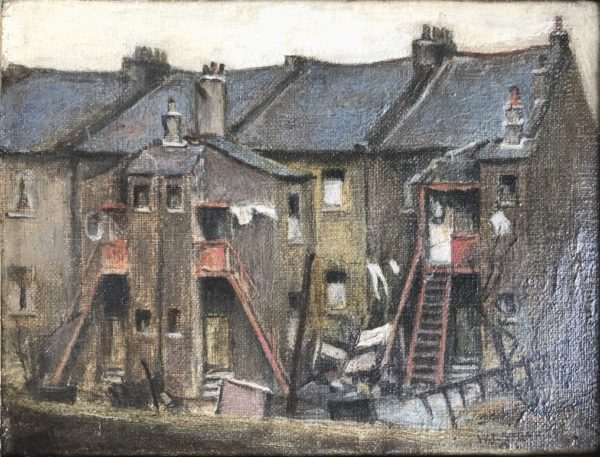

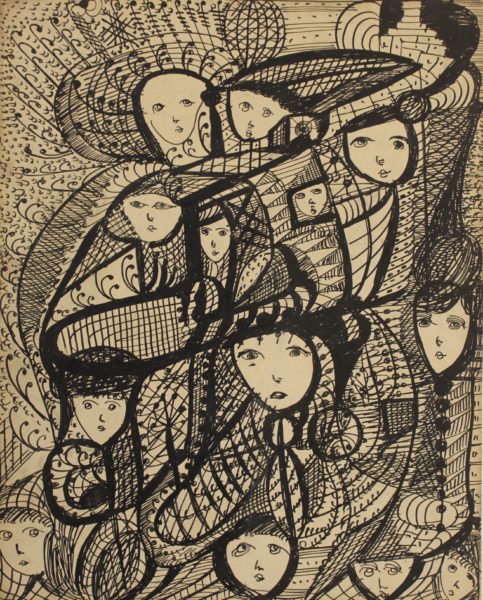

And that’s what I’ve taken from hanging these paintings together here: yes, East End art is about the buildings and the loss of them, the shops and markets, the poverty, even the beauty, but more than anything else I’ve realised during lockdown it’s about people and it’s about community.

You can see the video of the whole exhibition here:-